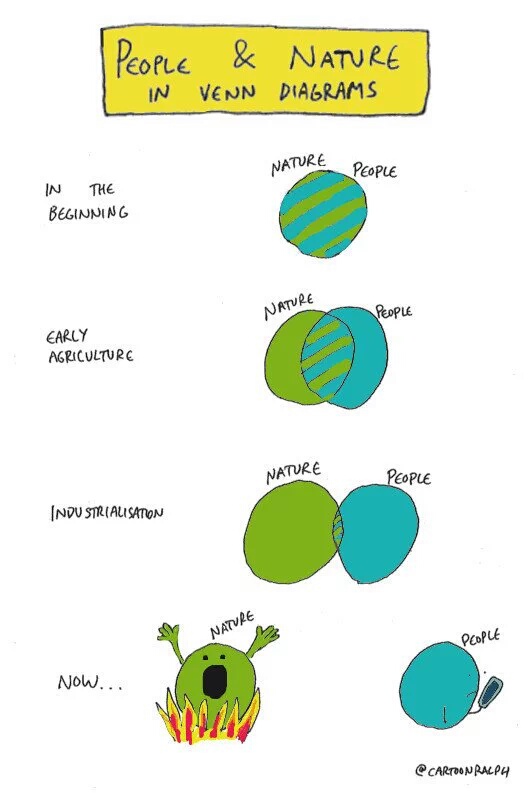

“Leave no ecosystem behind” was, for me, the standout quote from Aromar Revi during the UN DRR Global Platform in Geneva. What he emphasised was that it’s not enough to discuss ‘leaving no one behind’ or ‘leaving no place behind’, rather we need to start thinking about wider, systems-level impacts, and how our ecosystems are connected. This was closely followed by the stark reminder of we have less than 4,000 days to do something about it.

What does leaving no ecosystem behind mean?

During the week I heard: “we’ve ended up in a car crash— which leaves us with the challenge of how we accept the inherent uncertainty that characterises human existence, and how we can do something with it” (Kirsten Dunlop). Or, as Mami Mizutori put it, “risk is growing in a shrinking world”.

This highlighted to me that the long-standing issue is that systems-thinking isn’t baked into investment models.

How will we balance needs?

One example that surfaced throughout the week is the Tanzanian Selous Game Reserve. A hydroelectric power plant has been planned that will destroy at least 2% of the Selous Game Reserve, a Unesco World Heritage site and one of Africa’s last wilderness areas. The dam will be the largest in east Africa, and will inundate 1,200 sq km of land in the area. It will, undoubtedly, provide a large amount of ‘clean’ electricity. It will double Tanzania’s total power supply. This is an essential consideration in a country where ⅔ of the population currently resides without access to electricity.

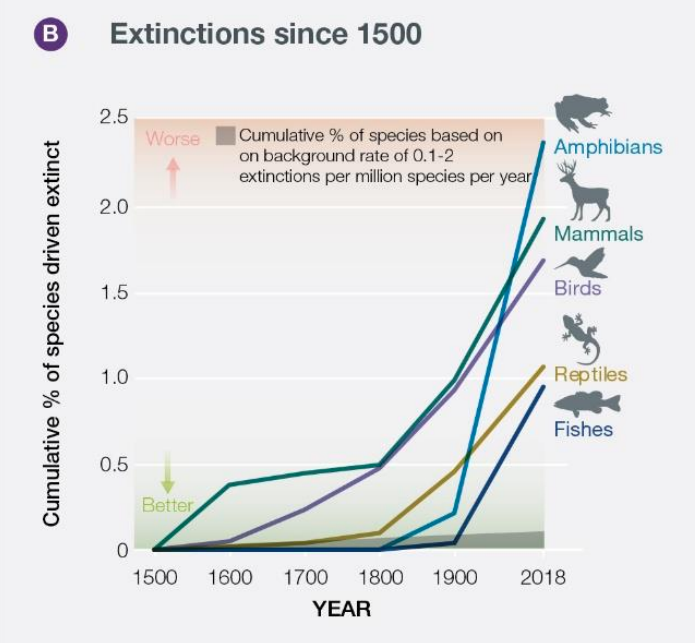

However, it will also vastly reduce biodiversity and accelerate species loss, at a time when 1 million species already face extinction, and affect the livelihoods of 200,000 people living downstream. The longer-term effects will result in greater downstream erosion, which will reduce the fertility of farmland and cause the Rufiji Delta to retreat. The result is that the OECD watch has declared the project unnecessary, and the economic and environmental costs too high to legitimately proceed.

This is without mentioning that the Reserve is home to elephants, rhinos, 350 species of birds and reptiles, and over 2000 species of plants. The elephant population alone has been dwindling since the 1980s (when it was at 100,000) – lower estimates now place the elephant population at 30,000.

What will the lasting effects be? Will the project contribute to the climate and biodiversity crises we face, or will it help us mitigate?

A fundamental question at the base of this is how do we incentivise a change in the way we model risk, to look be more forward-looking, to be more aware of the wider systems impacts?

To answer this question, I borrow again from one of the conference speakers: David Green of NASA. “We all own a piece of the solutions and we can make them stronger by bringing them together.” There is private sector applicability in the public sector, and vice versa. There is also a wide, immense base of information that could be used to improve our risk modelling, and bring in systems-thinking so that we can better understand the impacts. There are also places where there is no information at all.

The problem is that we don’t know where this information is, or if it even exists. There’s no easy way of searching for it, and if you do manage to find it, there is no easy way of understanding who can use it, and what for. Beyond that, there’s often no simple way of sharing it.

This need was echoed in all the conversations we had at Global Platform, by audiences, by exhibitors, by panelists and over casual coffees. We know the world is in climate crisis, and we’ve declared a data emergency. Icebreaker One is part of the emergency response.

We want to provide the collaborative framework to allow everyone to think about risk more systemically, so that we can, in the coming <4,000 days, leave no ecosystem behind.

We want to do this by inviting all stakeholders, from private, public, academic and NGO spheres to share their user needs and stories and collaborate to bridge gaps in information we are seeing.

The initiative is moving forward in a series of three steps:

- Step 1 (Global Programme Launch): initiate public conversation & alpha. Engage expert communities; draft principles, governance tools and technical standards.

- Step 2 (November 2019): public beta. Document and share standards and governance tools that are ‘good enough’; explore new data markets; engage countries to gather their requirements from a national strategic perspective.

- Step 3 (2020 – 2030): launch—put words into action. Build on open learning models to make sure stakeholders have the tools they need to discover, access and use data to address environmental risks, create and adapt financial instruments and invest in demonstrably more resilient infrastructure.

If you have a user story, or a user need, tell us your story. If you’d like to get involved, we want to hear from you – email me at gea@dgen.net.